Events during the third week of the Aftereffects and Untold Histories programme focused on performance art practices that are enacted in public.

DISCUSSION: Art in public

Brian Connolly, Brian Hand, Mari Laanemets, Kateřina Štroblová

Thursday 29th April, 4pm - 5pm

The third week of the programme commenced with a panel discussion exploring performative interventions in public space during the 1990s. Chaired by artist Brian Hand, the event featured short papers from artist Brian Connolly on his collaborative performance work in Dublin, art historian and curator Mari Laanemets on performances in the streets of Tallinn, and academic, art critic and curator Kateřina Štroblová on the Rafani Group in the Czech Republic. This was followed by a 20-minute conversation reflecting on the correlations and divergences among artistic practices and public gestures in the varying geographical contexts of Estonia, the Czech Republic and Ireland.

About the speakers:

Brian Connolly employs a range of artistic processes, including performance art, installation, public sculpture, collaborative and relational projects. In the 1990’s he developed a genre of performance art he called ‘Install-action’. He has created performance artworks and exhibited in diverse contexts throughout Europe, North America and Asia. He has initiated international projects and events and has been involved with artist-run organizations such as Bbeyond, The Sculptors Society of Ireland, Visual Artists Ireland, Flaxart, etc. He established the Belfast International Festival of Performance Art in 2013. He has been teaching Sculpture/Fine Art in The Belfast School of Art since the mid 1990s.

Brian Hand’s art practice is broadly concerned with creatively exploring and researching events, spaces, agents and ideas from the past. Hand has made many temporary public works and time-based installations, often in site-responsive ways. In the past, he believes, we can find alternative images that disrupt the naturalness of the present. Hand has worked on several collaborative projects with Orla Ryan. In the 1990s, Hand co-founded Blue funk, worked on the design of

the Famine Museum in Strokestown Park, and was recipient of the PS1 international studio residency and the Arts Council's critical writing bursary. Hand was curator of Critical Voices 2, worked for many years in Wexford and is currently Head of Department of Sculpture and Expanded Practice at NCAD.

Mari Laanemets is an art historian and curator, and is currently senior researcher at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Her research looks at alternative art practices in the Soviet Union in the late 1960s and 1970s and their intersections with architecture and design. She is interested in exhibition histories and the organisations of art in Eastern-Europe. She has curated exhibitions such as Abstraction as an Open Experiment, Tallinn Art Hall, 2018; Our Metamorphic Futures. Design, Technical Aesthetics and Experimental Architecture in the Soviet Union 1960-1980, Vilnius National Gallery, 2011-2012 (with Andres Kurg). She has edited: Abstraction as an Open Experiment, Lugemik 2019; Mladen Stilinovic. On Money and Zeros, 2008 (with Soeren Grammel); There Life Would Be Easy, Lugemik, 2010. She has published a book, Zwischen westlicher Moderne und sowjetischer Avantgarde: Inoffizielle Kunst in Estland 1969-1978 (Gebrüder Mann Verlag, 2011) and contributed to ArtMargins, Camera Austria, Rethinking Marxism, Springerin and many collected volumes and exhibition catalogues.

PhDr. Mgr. Kateřina Štroblová is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Theory and History of Fine Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Ostrava (CZ). In her research, she focuses on contemporary art practice of East-Central Europe, mainly on post-communist conditions in various regional contexts. Based in Prague, she is also a freelance art critic and reviewer and an independent contemporary art curator. Since 2010, she has been working as chief curator and project manager in Luxfer Gallery, an independent experimental art space and studio in Česká Skalice (CZ).

SIDEBAR CONVERSATION: Mapping Performance Practice in Ireland

Kate Antosik-Parsons, Jennifer Fitzgibbon

Friday 30th April, 2pm - 3pm

Contemporary art historian Kate Antosik-Parsons discussed her research and highlights from her interviews with seminal Irish performance artists including Brian Connolly, Pauline Cummins, Sandra Johnston and Danny McCarthy, which were specially commissioned by NCAD for the Aftereffects and Untold Histories programme, with NIVAL Administrator Jennifer Fitzgibbon. Antosik-Parsons has conducted and documented in-depth conversations with key artists whose names are associated with the development of national performance art practices since the late 1970s, 1980s and 1990s that capture the rich layers of oral histories that surround performance practices in Ireland. Her research consulted major art historical publications, archival and primary source material held in NIVAL, the Project Art Centre Archive in the NLI (Dublin), and in personal artist collections.

This conversation had a limited attendance and was not open to the general public to encourage conversation and the exchange of ideas. Participants were invited to join in the conversation and keep their cameras on for the duration of the event.

Selected key excerpts from Kate Antosik-Parsons' interviews with leading Irish performance artists Alanna O'Kelly, Anne Seagrave, Brian Connolly, Brian Hand, Danny McCarthy, Fergus Byrne, Fergus Kelly, Frances Mezzetti, Pauline Cummins, Sandra Johnston, and Seán Taylor can be found at the bottom of this page.

About the speakers:

Dr Kate Antosik-Parsons is a contemporary art historian and a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in Trinity College Dublin. Kate was the L’Internationale researcher for NCAD’s ‘Performance Art in Ireland in the 1990s’ project (2019-2020). Her research is concerned with gender, sexuality, embodiment and memory. Kate’s recent writings include essays on pain in Máiréad Delaney’s At What Point It Breaks (2017); embodied politics in contemporary Irish art and visual culture; Irish women’s citizenship in Amanda Coogan’s Floats in the Aether (2018-2019); abject femininity in the work of Willie Doherty; and touch and haptic encounters in Irish performance art. More information about her work can be found at www.kateap.com

Dr Jennifer Fitzgibbon is the administrator at The National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL), a public research resource dedicated to the documentation of 20th and 21st-century Irish visual art and design. NIVAL collects, stores and makes accessible for research an unparalleled collection of documentation about Irish art in all media. NIVAL’s performance art collections consist of files on artists, subjects and venues as well as Special Collections on artists such as Brian Connolly and organisations such as Women Artists Action Group and Temple Bar Gallery & Studios.

Housed in NCAD and resourced through a strategic partnership between NCAD and The Arts Council, NIVAL is committed to making our collections accessible to everyone for exploration, education and research. NIVAL sustains its collections through active collaboration with artists, designers and cultural organisations. Its collection policy includes Irish visual art from the whole island as well as Irish art abroad and non-Irish artists working in Ireland. Information is acquired on artists, designers, galleries, arts organisations and institutions, critics and other related subjects. The collection contains documentary material in all formats including books, catalogues, videos, slides, artists’ papers and ephemera in print and digital format and is central to NCAD's commitment to supporting new thinking and research in the fields of contemporary art and design.

DISCUSSION: Political performance in Yugoslavia during the 1990s

David Crowley, Vida Knežević, Nita Luci, Bojana Piškur

Friday 30th April, 6pm - 7:30pm

David Crowley (NCAD) chaired a conversation between art historian, curator, cultural worker, and member of Kontekst collective Vida Knežević (Belgrade, Serbia), feminist scholar Nita Luci (Prishtina, Kosova), and curator Bojana Piškur (Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana). The contributors discussed political performance of the 1990s in former Yugoslavia, addressing the challenges of researching performance from a highly contested period of history. The group explored the characteristics of performance practice among the different territories and the issues that arise when exhibiting such work today.

About the speakers:

David Crowley is the Head of the School of Visual Culture at NCAD. He is a curator and historian with a specialist interest in the culture of Eastern Europe under communist rule. His most recent show, Notes from the Underground. Alternative Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1968-1994 (co-curated with Daniel Muzyczuk in Łódź in 2016 and Berlin spring 2018) reflects his interest in the intersections of music and visual art. His book Ultra Sounds. The Sonic Art of Polish Radio Experimental Studio was published in 2019.

Vida Knežević is an art historian, curator, cultural worker, and member of Kontekst collective whose work is based on a process of connecting critical theory and practice, and the field of arts and culture with wider social and political effects. In 2019, she completed her PhD thesis entitled ‘Theory and Practice of the Critical Left in Yugoslav Culture (Yugoslav Art Between the Two World Wars and the Revolutionary Social Movement)’. Since 2014, she has been one of the editors of the educational project and the left online magazine Masina.rs, where she deals with the relationship between cultural, art and media production, economy, politics and activism.

Nita Luci is a feminist scholar. She teaches at the University of Prishtina and is chair of the Department of Anthropology. Her scholarship has focused on the intersection of nationalist cultural politics, manhood, memory and heritage, violence and political movements. She co-founded the University Program for Gender Studies and Research, has co/led teaching and research projects (Memory Mapping Kosovo; Gender and Sexuality Summer School; ReContextualizing Contested Heritage); and contemporary art initiatives (Women n/or Witches: Representation, Feminism and Art supplement; Protest, Imagery, and Art course; Missing Identity project). As Co-I on the ACT project (GCRF ‘Changing the Story’) she is part of a participatory collaboration that interrogates ways in which artists, arts organizations, initiatives and institutions engage young people with and through arts on civic education, heritage and social justice.

Bojana Piškur works as a curator in the Moderna galerija in Ljubljana. Her focus of professional interest is on political issues as they relate to or are manifested in the field of art, with special emphasis on the region of (former) Yugoslavia. Her most recent exhibition dealing with the topic of

the non-alignment was Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned, Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 2019 and Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, South Korea, 2020. She is currently working (with colleagues from the region) on a research project and exhibition REALIZE! RESIST! REACT! Performance and Politics in the 1990s in the Post-Yugoslav Context.

NIVAL ARCHIVAL SELECTION/ARTIST INTERVIEWS

The National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) is a public research resource dedicated to the documentation of 20th and 21st century Irish visual art and design. NIVAL collects, stores and makes accessible for research an unparalleled collection of documentation about Irish art in all media. NIVAL’s performance art collections consist of files on artists, subjects and venues as well as Special Collections on artists such as Brian Connolly and organisations such as Women Artists Action Group and Temple Bar Gallery & Studios.

Housed in NCAD and resourced through a strategic partnership between NCAD and The Arts Council, NIVAL is committed to making our collections accessible to everyone for exploration, education and research. NIVAL sustains its collections through active collaboration with artists, designers and cultural organisations. Its collection policy includes Irish visual art from the whole island as well as Irish art abroad and non-Irish artists working in Ireland. Information is acquired on artists, designers, galleries, arts organisations and institutions, critics and other related subjects. The collection contains documentary material in all formats including books, catalogues, videos, slides, artists’ papers and ephemera in print and digital format and is central to NCAD's commitment to supporting new thinking and research in the fields of contemporary art and design.

Kate Antosik-Parsons has selected key excerpts from her interviews with leading Irish performance artists Alanna O'Kelly, Anne Seagrave, Brian Connolly, Brian Hand, Danny McCarthy, Fergus Byrne, Fergus Kelly, Frances Mezzetti, Pauline Cummins, Sandra Johnston, and Seán Taylor. Related documentation specially selected by Jennifer Fitzgibbon from the archives at NIVAL will be published alongside the texts. The full-length interviews are archived at NIVAL and can be accessed by contacting nivalinfo(at)staff.ncad.ie to make an appointment to view the transcripts.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: I wanted to ask you about your participation in ‘Available Resources’ (1991) which Brian Connolly organised through the Orchard Gallery, Derry. I think your work there was called ‘A Resounding Well’?

Alanna O'Kelly: Yes, it was called ‘A Resounding Well’. What happened was I had been invited and was really aching to take part in the show with Brian. I had a very young child, I was feeding him at the time, and Brian facilitated that I could come with the child. I brought my eldest son with me and I brought Julie Joynt, Rachel Joynt’s sister, to help me. Julie came up with me and this young child, and took part in the workshops and the performance. I had been in Derry before, and I'd made a piece of work in Derry. My very first kind of public piece of work was made in Derry in Limavaddy People’s Park (1979) and later ‘One Day … In Time (Extracts from Una O’Kelly’s Diary November 1981-1988)’ (1988).

I knew the scene up there in the city, and I asked would it be possible that I could work with both communities. They made it possible for me to work with a women's group, so I worked with both communities. With this small group of women, we decided we would go to An Grianán of Aileach, which is actually not in Derry, but just outside in Donegal. We decided to go there for early morning, and do the performance there drawing on the workshops that I had done with them. I had also invited other artists who were part of ‘Available Resources’ like Anne Bean and Fran Hegarty. They hadn't been part of the women's workshop group, but they came along to the performance, to this kind of gathering. So it was mighty, and, of course, I didn't have photographers but I had my own camera and somehow people had taken photographs, so I have a couple of odd photographs of the performance.

KAP: I think I have seen two photographs. So An Grianán of Aileach is a prehistoric fort?

AO'K: Yes and it was great for sound. It was this lovely kind of sacred space to be making sound in.

KAP: It sounds pretty special. How many would you say participated? What would you estimate the number?

AO'K: I don't think all the women were able to come, because they all had families as well. But I think judging by the image only because I can't remember at this moment, I think I probably had 12 for the workshop, and I might have had about 10 or 12 at the performance. It was very early in the morning, we went for sunrise. It might have been a half an hour, or something like that.

KAP: Okay. It sounds like you were doing a lot of vocal workshops around this time?

AO'K: I did some in Belfast as well, and it was a way of connecting with people. I was doing a little bit of teaching at the time. I was trying to find my own voice. I was really interested in voice and sound work, and people were doing like... People who were doing sound work in Europe, and I was listening to some of this and I was very interested in how deep the sound can go. It can go very deep very quickly. Sound can go there really quickly. I was interested in that, but I was also interested in it as a new mode for me. A new medium in a way. And so as I was trying to find my own voice, I realised people kept asking me to do workshops. So I ended up doing those things. I did a workshop in Belfast and then decided when ‘Available Resources’ came that I wanted to make something with people there. It was literally available resources, there was nothing, nothing, nothing. It was get up there, make a piece of new work, and see what happens after you do so. It was very interesting. It was challenging as well.

KAP: What did you think about the kind of atmosphere there for performance artists? I guess what I'm trying to ask is how did an event like that help to support emerging artists?

AO’K: You know, it gave us a platform to work. Derry is a very interesting city to work in. It wasn’t my first time as I’ve said, but it brought international artists alongside artists from around the country, North and South. Brian was brave, with only available resources he brought us together and managed the event. And I guess we all brought and shared a lot of resources from within ourselves. But I do remember being in this conversation, I had a small child, so I wasn't up late socialising with them or anything. But there was talk about, ‘Oh, I'll see you in Poland,’ or, ‘I'll see you in Mexico,’ or, ‘I see you in...’ And there was something about this tour of performance work that I just thought that is not where I am. It's not really... Some of these artists I admire greatly. I love their work, but it wasn't ...I just wanted to run a mile from that.

KAP: But some of it also isn't always feasible when you have a young child.

AO'K: No, it's not feasible. It wasn’t that they didn't have young children, but it was not feasible for me at that time. There was nobody to hold up the scene for me to head off. It was just that I was on a different trajectory. I did see some live work that was done at midnight, or at different times in spaces around Derry City, and I was very taken by it. It was powerful stuff. But I realised I was looking for something else with these women. I was trying to cut through something. I wanted to get out of the city, go to some ancient site, try to do some contemporary work and bring something new there. In that situation that was important to me.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: It also seems like at a very early stage of your career you had broad exposure to lots of different performance artists and performance art platforms at clubs and festivals. How do you think this informed your own work organising artist-led workshops, once-off and recurring performance nights in Ireland in the 1990s? I'm thinking specifically of events you organised as part of Random Access/SSI or later through Arthouse.

Anne Seagrave: I actually first started organising performance events in London in 1987 in a room above a pub. My philosophy was always, organise good cheap publicity, pay everyone the same, treat everyone the same. I organised workshops and events in Ireland mostly in conjunction with other artists (SIN SIN, Oscar McLennan) or organisations (Sculptors’ Society of Ireland (SSI), Arthouse, Dublin Fringe Festival, NCAD, Limerick School of Art). It was really hard work, but a lot of fun, very rewarding, full of surprises. I had quite a talent for organising events because I was very energetic, positive, very hands on, I could always manage to get equipment we needed for free for example through contacts or friends. I was always very influenced by the so called ‘pitch in culture’ of the artistic community in Poland during the 80's. Basically, everyone pitched in and the art took place.

KAP: You moved down to Dublin in 1989 – what were your impressions of the performance art scene in Dublin at the time? Tell me about your involvement with Random Access? How do you think artist-led initiatives like Random Access advocated for expanding understandings of process-based, or time-based performance practices?

AS: I had actually presented a performance in Dublin in 1985 in the Guinness Hop Store, so as a consequence I was a little familiar with the very small Dublin performance art scene when I moved there in 1989. I have always mixed with performers of many disciplines, styles and techniques so it didn't really bother me that there were very few performance artists devising work in Dublin at that time. The economic situation in Ireland was grim. It was very hard to survive. I participated in a government run job scheme with the SSI, and so became involved with Random Access. As I knew many artists from London personally, I was able to call for example, Helen Chadwick, Bobby Baker and Mona Hatoum, and invite them to the Random Access Time-Based Art conference at IMMA.

Most of my memories from around that time are full of art, activity and poverty together. I had a very small income. It was often cold and very hard to manage. Artist-led initiatives like Random Access addressed the concepts and the art practices, but not the problem of how does the artist survive when there is no tangible ‘product’ for sale as a result of their work. In fact, the value of performance practice as a discipline is its ability to question the importance and relevance of the art object, the art product for the art market, and who this benefits.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: I want to talk a little bit about your collaborations because I think it seems to be an important part of your performance practice during this time period. I know that you had several collaborations with Maurice O’Connell. Could you tell me about them?

Brian Conolly: Yes, a very fond time. With Maurice, you realised very quickly that he was special, he was a complete one off. I saw his degree show in NCAD in the early 90s.

KAP: Were you living in Dublin at the time?

BC: I was working in Dublin at the time and it was Leo Higgins I think mentioned Maurice to me – that I should go see the show because of the time-based element. So I went along and I just was blown away. I said this is some character.

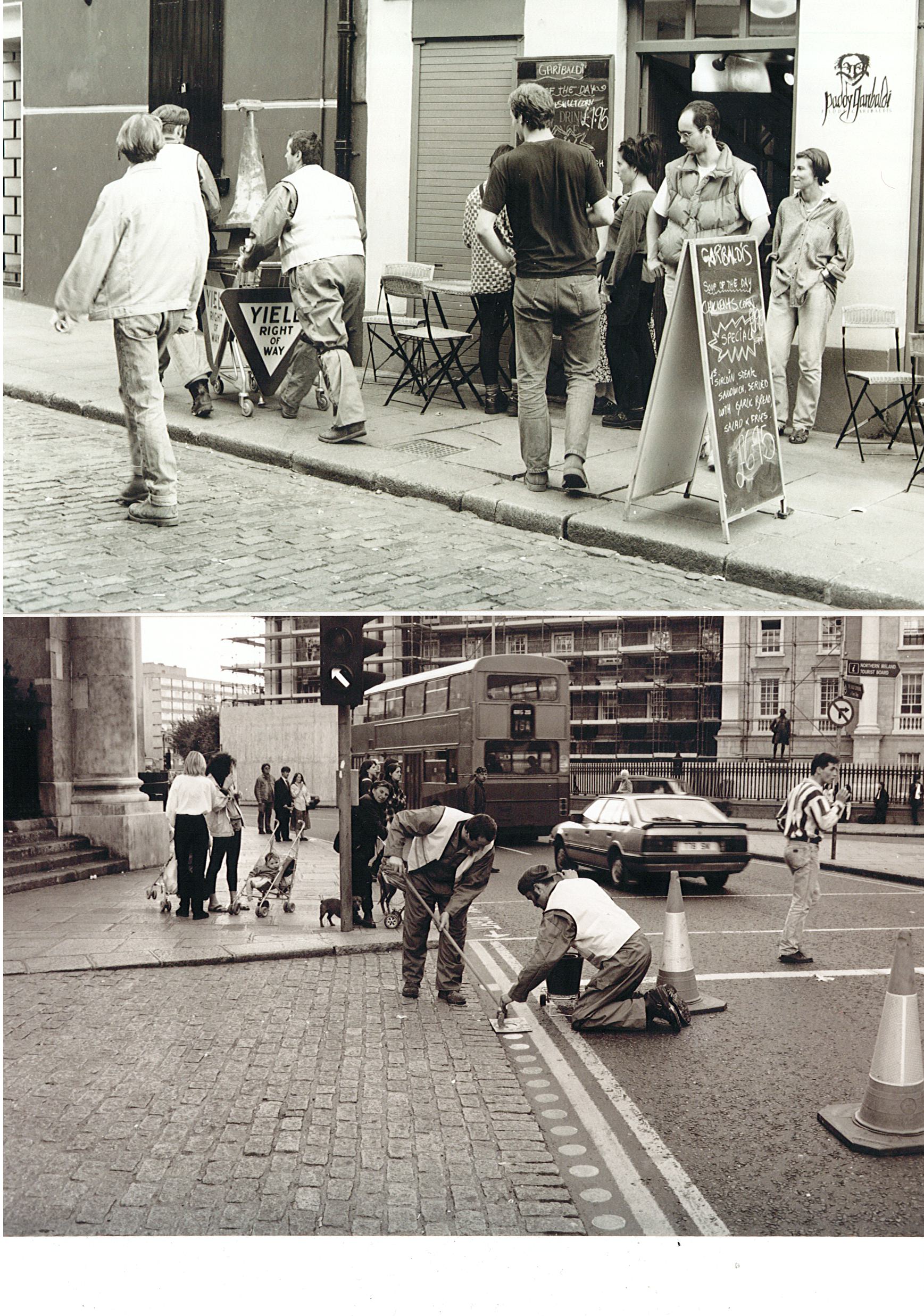

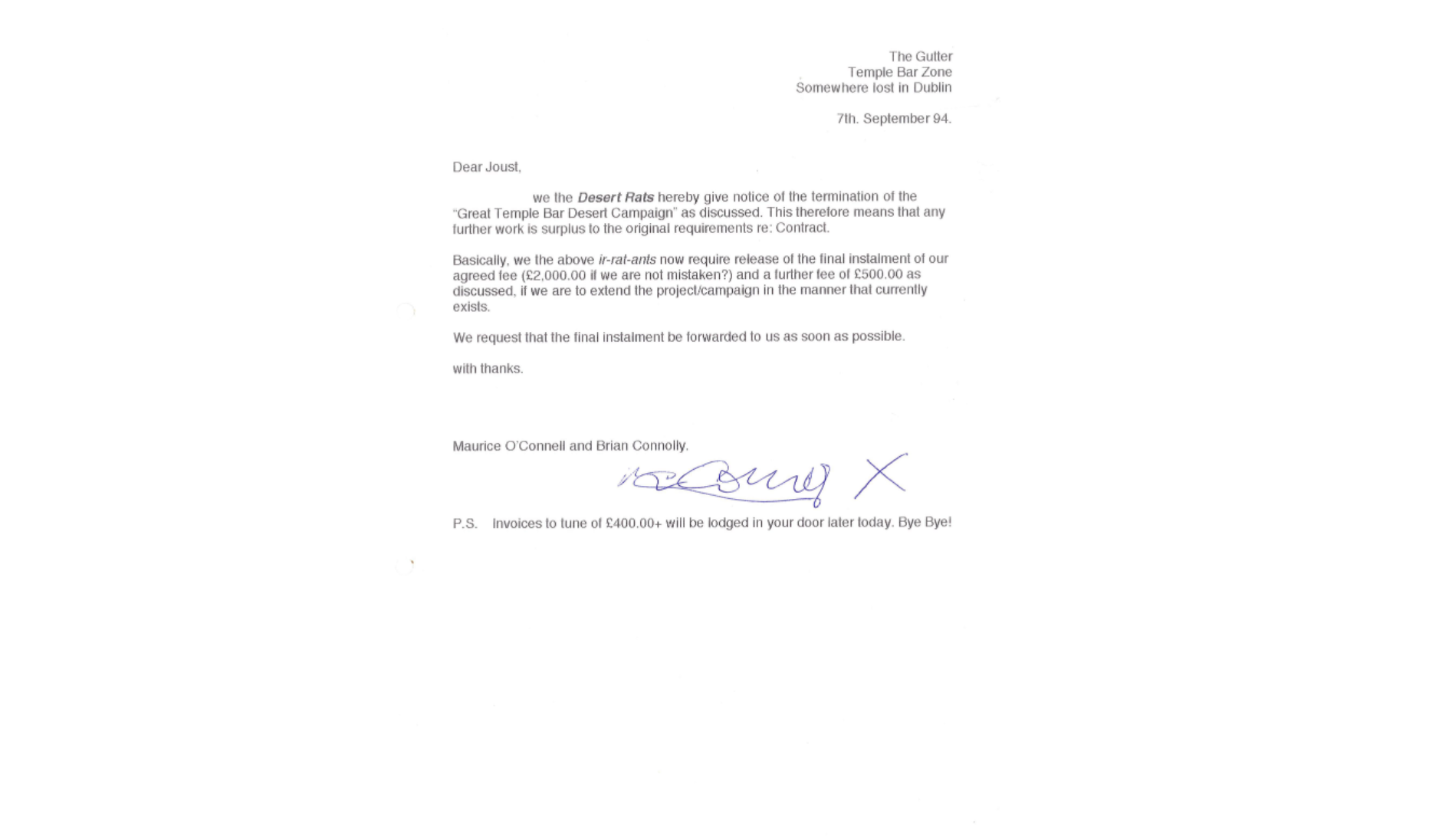

Basically through conversations and good humour we would have come up with several little sketch ideas, and later on we were approached by Jobst Graeve, he was working with Temple Bar Properties, developing it into whatever it is now. I had come through the era of knowing that there was lots of studios and artists, literally lots of artists existing in Temple Bar because it was run down, and people had the possibility to live there and have studios there. That was the context I was coming from. I felt that Temple Bar was kind of using that idea of evolving property development portfolios with European funding and basically using culture and art as the means of getting the money, but in the long run not helping the culture that generated the interest in the first place. I had my questions or criticality about that whole process, so whenever Jobst approached me and Maurice, we were talking about these things, and Maurice was pretty adamant about the same things. Jobst asked us to come up with something that would celebrate the entrances to Temple Bar, and I sort of said celebration wasn’t really the word I would be thinking of.

KAP: I have actually come across the proposal in the Artsource boxes in NIVAL. When I read it, it is so critical of Temple Bar and how it was being pitched at the time. This is the description: Drawing a dotted red line around the whole area of Temple Bar, in places scissors motif will be used alluding to the cut away aspect of two-dimensional mapping construction. Cut along the dotted line, text such as Temple Bar and then the Republic of Ireland.

BC: On the maps, at the time, their own promo, they [Temple Bar Properties] were using the dotted line around the whole Temple Bar area. And this idea of it being separate. We just amplified how they were viewing it, that it was a separate zone. We just amplified the ideas that it was seen as a separate part of the city. That was our initial approach and we kept telling stories while we were out in the street doing the job.

KAP: Did people actually stop to ask you what you were doing?

BC: Yes. We went out periodically, we didn’t go out every day – working with Maurice’s schedule – we would go out whenever he was available. Sometimes it might be twice a day, sometimes one evening, maybe sometime mid-day. So we were really hit and run, like really hitting and running. We had evolved the worker’s cart out of a shopping trolley, a fire bucket etc, etc, we had robbed signage.

KAP: I have to show you here… there were multiple photos in the file - you can see people looking and saying, ‘what is going on here?’ You look so official.

BC: It’s something I talk about – that all you need is a boiler suit and a security jacket or a high vis jacket and a pair of boots. I mean we did get chased twice, by the police. Once was a Ban Garda shouting at us and we were off with our trolley like a shot. I was also told to remove myself by another guard once. Because we blocked streets, we actually stopped traffic and we painted the dots and made traffic wait and you could just see, ‘What the fuck?’ And there is a brilliant photograph I have of a work man coming out of a pub being renovated and he was obviously the gaffer, the boss, and he came out, because we were just outside the door, and there is a great photograph of him, standing up to Maurice. He was talking to him and basically the conversation went like, ‘right lads what the fuck are yous on about?’ And he didn’t even come in and see us as workmen or anything, he just saw through us, he could see the coding was there, but he knew we were messers. And he just cut through the crap, like ‘what the fuck are yous at?’

People would just read it as normal that we were doing a job, some sort of realistic job, that someone was telling us to paint these dots and people were wondering what they were. We were spreading all kinds of stories, like this is now a separate zone, these reds dots signify that this is a different part of the city, and there is talk of passports, there is talk of how taxis won’t be able to come in here after certain times. So we were just kind of spreading rumours about separation and difference. What makes this part of the city different from another part?

KAP: How do you think that translates into the context with the North? Does it?

BC: Aye, for me it does anyway, the illusion of the border.

KAP: All this talk about Brexit now with the hard border possibly coming back. It’s just so interesting looking at something like this, it is so arbitrary as drawing lines on the map.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: In 1990, you were the artist in residence at Kilmainham Gaol and it’s my understanding that you were the first artist to approach Kilmainham as a site for artistic response. Can you tell me a little bit about that, and your use of history in your work and archives, the importance of the research process there?

Brian Hand: I had a tutorial with a really interesting artist, Martin Folan who made some very lovely work and was exhibiting in the Irish Exhibition of Living Artists (IELA) regularly, including the exhibition I was in (1986). He came and gave me a tutorial and I talked to him about Kilmainham Gaol. I said that I was really interested in Kilmainham Gaol/museum, I had been visiting it since I was a child, because my grandfather was a prisoner there. The Office of Public Works had taken it over in 1986 or 1987. I saw their tape slideshow and it was a nonsense narrative of Irish progress. I thought I could make a pastiche of this. And he said that would be quite a big thing to do, but you could go to Kilmainham Gaol and be an artist in residence. He planted the seed. He said you shouldn’t just hypothesize about this you should go do something about it. It stuck with me.

As soon as I graduated, I wrote to Pat Cooke and Medb Ruane. […] Pat Cooke said come in and talk to me about it. He said, put it together as a proposal and I will consider it and I’ll talk to Medb Ruane. I put together a proposal, I was explicit in saying my grandfather had been a prisoner there and I was interested to find those connections, but I wanted to do something on the history of secret societies and the history of secrecy. How do you write a history of people who don’t leave any trace – are they present or are they not present in the history? And yet they seem to be present because every time there was a rebellion you add another wing onto the prison. I thought this place would be an interesting place to look at because the history of the prison itself is of a secret society and as a hidden, closed world. I thought it would all fit well to look at this through a lens-based approach, I didn’t know what it was going to be, except, I wanted to be there for six months.

I wrote a budget and said I wanted them to pay me £5000 – £2500 from the Arts Council and £2500 from the OPW. Amazingly, they had a meeting together and invited me in and said yes. I’m not trying to be smart but 5000 pounds in 1990 was a really generous residency. I started there in February and finished in September and I had a show. I really worked hard and used every ounce of my time there. I made this big show in the old wing. The works were videos, sound works, props, etc and some people who visit Kilmainham like a shrine made comments in the visitors’ book along the lines of sacrilege – they hated it. Lots of Northerners who came to visit – they said what is this?

KAP: It sounds like you challenged their perceptions about the meaning of that space.

BH: I used to give tours of the place. It was this standoff between the old guard and the new OPW staff coming to give the tours. The old guard were the dedicated volunteers who had always been doing it and knew everything, including this woman who had written this book. She collared me as soon as I walked in and said, ‘I’ll tell you exactly what Kilmainham Gaol is all about’. If I had been not so fascinated by the subject of itself, I could have done a fantastic work about the staff and the human dynamics that were going on in that place over history. It would have been a different kind of piece you could have made. I wasn’t able to do that, I was still the archive nerd, the finding of material. They had just appointed an archivist. I found my grandfather’s prison photograph. I found his other material that had been donated; his prison badge and prison hat. There was so much. I could have stayed there for a decade making art.

KAP: It’s compelling to think about having that amount of access to information, even to the space itself, to have the time to spend in that space and to get to know it in an intimate way.

BH: Yes, that’s right. My room ended up being called the Hand Room. After I’d gone, I’d go back to visit them to catch up. John Toolan who became the manager after Pat, he’d say, ‘Oh yeah we have great fun with the new guys, we tell them, “that’s in the Hand Room”. And then one of them said “Was he a patriot?”’ (Laughs) During the residency I lived nearby on Infirmary Road and I spent so much time there - I used to stay the night there, I just had the best time, it was fantastic experience.

I was really influenced by Benjamin’s Arcades Project (1982), at the time it was before proper translations came out. When I was in college, I was reading The Origin of German Tragic Drama (1925) and Peter Dews The Logics Of Disintegration (1987). I was able to present on each cell door in the Victorian panopticon wing a collage of different texts, which I felt was trying to get this methodology of the Arcades Project. That was the challenge using texts to try to make new connections but acknowledging all these different voices that come into it. The piece was also made from light boxes, you had to look in each of the spy holes, the mounts and covers of the spy holes themselves were mirrors, so that you see your eye before you pull back and inside were a range of image-based work as well as video pieces, projection pieces, one spy hole blew a blast of air back at you. And then light boxes inserted into this oval frame, which was in behind. Then above the door I stencilled the names of about twenty-four different secret societies in Ireland in the 19th century, like Ribbonmen, Shanavests, Caravats and Rockites. I really liked this idea of this proliferation in front of this sort of secret history that doesn’t seem to figure out - how do you put this together? How do you acknowledge this, this history which isn’t one or singular? It disrupts the narrative most likely through violence, or threats of violence, regionalism and a host of other factors.

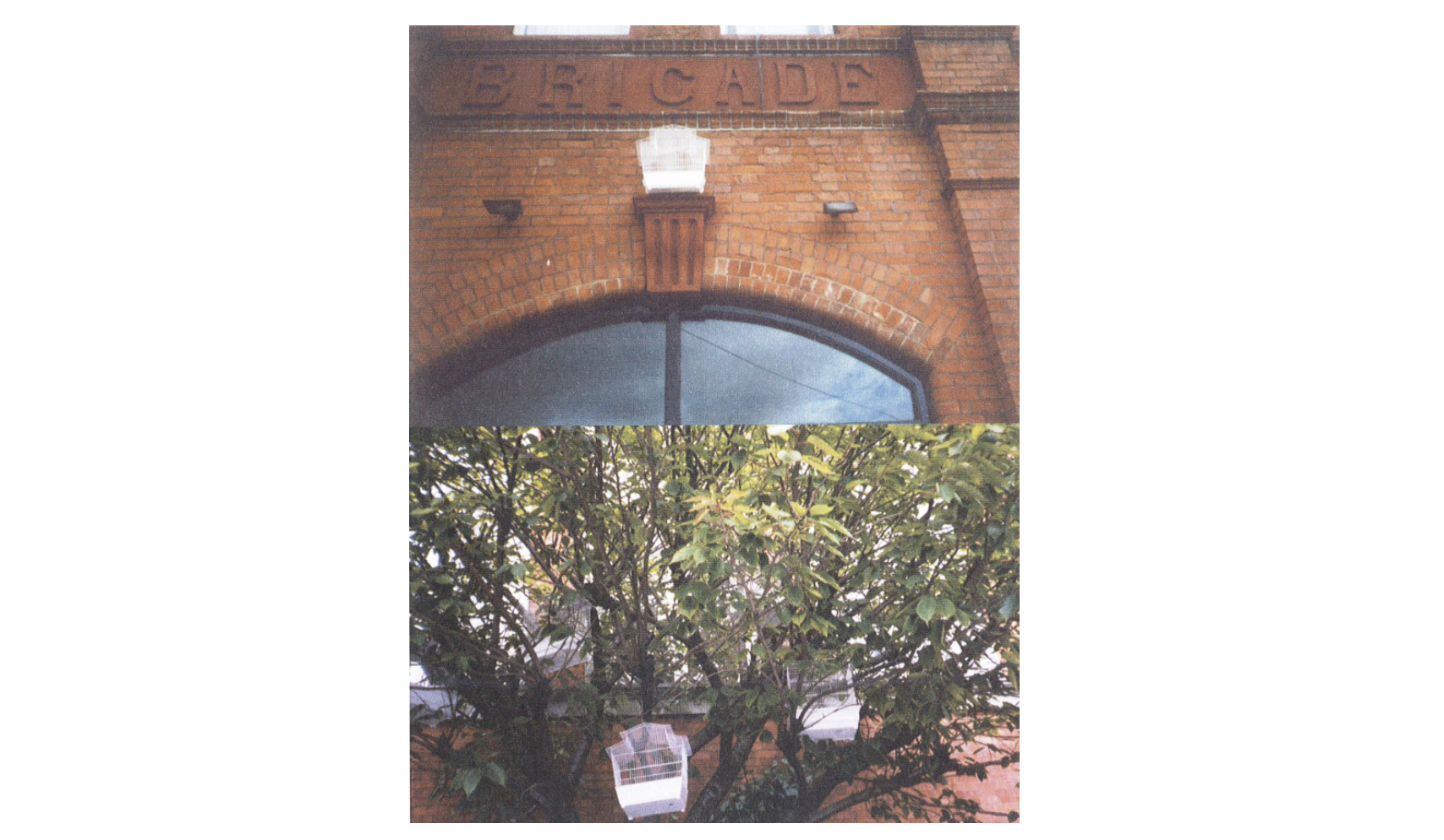

Kate Antosik-Parsons: I wanted to ask you about ‘The Birdcages of Dublin’ (1997) which was for ‘Inner Art’. I believe Tony Sheehan was the curator at Fire Station Artists’ Studios at the time. Can you tell me a little bit about the ideas behind the work and the development of it?

Danny McCarthy: I always talk about this work when I am teaching. Basically, the piece consisted of five birdcages along the outside of the Fire Station, spaced out. Five white birdcages, each cage contained two speakers. The initial idea for the piece came from people having birds at home, and in the summer people would take their birds, their finches or canaries and put them outside their house so they get fresh air and they would be singing outside the house. It’s a practice that is still going on around Cork up in Shandon. If you walk up there on a summer’s day you will find some of the old, smaller houses with the birds outside. When I walked around inner city Dublin, down Buckingham Street, it struck me that this might work. It was very much a community-based project.

I thought maybe we might get people to put my birdcages with the speakers outside their houses. But it didn’t really wind up being practical so we moved them down to the Fire Station and put them up outside the front of the building. It consisted of field recordings I made of Dublin that I blended together on one tape and then birds singing on the other. The whole thing was indeterminate in that the sound would be changing all the time. The way we did that with the technology was that you got a 30 minute tape and a 45 minute tape and they would both play at the same time. The 30 minute tape would be back at the start by the time the 45 minute tape would be at 31 minutes. It was different all the time.

KAP: It was always changing?

DM: Always changing. I think there is some mathematical permutation that it will come back in synch but I don’t know what that is.

KAP: It would take a while. (Laughing) I can’t do that math!

DM: It would take a while. The sound was tending to move from cage to cage up the front of the building. Again, going back to older technology, it was all analogue. I had two cassette players on auto reverse and they were plugged in so they could keep going all the time. They were all in a timer that you could plug into the wall and start at 8 o’clock in the morning and finish at 10 o’clock at night. They didn’t need any human intervention for the duration of the piece. But I happened to explain it to the caretaker of the place, just in case there was a power cut and he had to start it up again. He figured it out pretty well how to work it, but then afterwards I heard what he would do when he was on the night shift, when the lads would be coming home from the pub at 11.30 he’d turn on the sound of the birds. The lads would be walking up the street half-pissed and all these birds singing.

KAP: They probably thought it was a flock or something!

DM: It was quite fun.

KAP: The sounds of the field recordings, were recorded from that area of Dublin?

DM: Yes they were from around inner city North Dublin. There would be some bits of it where you might get the boy racers and you would get the boom boom bass of the cars. The sounds of metal being scraped. All those sounds. An interesting story is, I got invited to do it in Cork. So I did the ‘Birdcages of Cork’ using sounds from Cork along with the same birds. Then ‘EVA’ was on in Limerick, so I submitted ‘Birdcages of Limerick’ and it used the sounds of Limerick. I think I did it in Budapest as well.

In Dublin it lasted for a month or 6 weeks. In Cork, it was due to last 6 weeks in the Crawford, it lasted two weeks. It was on the big trees outside the Crawford and someone climbed the railings outside and stole two of the birdcages on a Saturday night. In Limerick, it lasted a week and a bit and again, someone stole one of the cages. The interesting thing is when I went back and asked Tony, ‘All this has happened, how come it wasn’t touched in Dublin?’ Tony said, ‘If anyone touched it, they would have been fucking killed.’ Because the community were really involved in the whole project. Other artists like André Stitt did work as part of that project as well, they were really involved with the community.

KAP: So the community was really invested in the work?

DM: Yes they were really invested in it. When the work was shown outside the two municipal buildings it was damaged.

KAP: Do you think it was people that… okay this is just speculation, but do you think it was people that were annoyed by it or was it just people that were messing?

DM: Messing I would say or just wanting a birdcage. People wouldn’t be annoyed by it because it wasn’t … Neither of the two situations would have been anywhere where the sound was interfering with people. It would just be passing. There is no accommodation near enough to the Crawford and there certainly wasn’t in Limerick because it was just outside the city hall and it was enclosed at night. It would have been visible and audible during the day.

KAP: How loud were the sounds?

DM: They wouldn’t have been terribly loud by any means. Loud enough to be audible but certainly not intrusive.

KAP: So if someone was walking past then…

DM: They would hear it.

KAP: Would it be just like a ‘oh hang on what’s that?’ or would it have been more noticeable? I don’t know how to describe listening levels.

DM: Once you tuned into it, it would have been quite noticeable. But not so noticeable that you couldn’t conduct a conversation. It wasn’t that loud.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: I was looking at the 1998 ‘EVA’ catalogue and there was a quote included with your work, ‘Following the death, Gardaí issued an appeal to young people not to engage in aggressive behaviour, however unintentional’. That’s from the Irish Times in November 1998. What was that referencing?

Fergus Byrne: Yeah, so that was actually a piece that I did called ‘Headguard’ (1998), and that was done with what had by then become a head guard, which was the same bicycle tubes around my head. The quote was from an Irish Times article reporting on a death that had occurred in O’Connell Street, in Limerick. Two guys who had known each other, they were friends, whatever kind of fight or mess they got into... One hit the other, and one fell on the ground and died because he banged his head. And I found the quote was very interesting, just this notion of not to engage in aggressive behaviour, however unintentional.

And it made me think about, ‘Well, when does behaviour become aggressive?’ And is it even after the fact that it’s deemed aggressive because of what happened, or up until that moment is it all just fun and games, or whatever? I mean, I don’t know if these two guys actually had a fight, but anyhow, there was something in the wording of that quote, which I thought was very unusual. It made you think on different levels about the words.

I did a piece, ‘Headguard’. I had a concrete sandwich board made with that quote written on it. The concrete sandwich board was to draw attention to the concrete, that they’d fallen on. Concrete sandwich board as a notice, but a very oppressive object to be wearing, and it in itself limits your movement.

KAP: I like this idea of the sandwich board as public advertising, in the same way that Gardaí might put out a public appeal, like it says here for people not to engage in aggressive behaviour but again, it’s that weight on the body, and the restricted movement... Because, I suppose, the head guard would’ve restricted your vision as well?

FB: Yeah, that was pretty ridiculous performance, like, I mean. Doing it in ‘EVA’ was all very easy, like, I did it a few times since, but I found in ‘EVA’ I really had to question it. I think it was maybe the first time I did it, but I did a whole... It’s done at the opening, they encourage you to do it at the opening of the show, so you have a whole crowd of artistic people around you, which is all very protective. I’d done another performance at ‘EVA’ where, you know, it was more... There was more sense of the public having some leverage in this. And also, that I didn’t know the guys. And as it happened, it turned out I’d done the performance very close to where the incident had happened, which I didn’t know. But someone had said, ‘Oh, that’s amazing,’ and I thought, ‘That’s coincidence.’ There was nothing like, in the ether going on. I didn’t know the people. It’s still about the quote, and I still have the blocks, the sandwich board, and I still think the quote is interesting.

So, I did it subsequently in Dublin, with less of a big crowd around. Well, no crowd. And I did it soon after the... So long ago, there was that Mayday week party in the streets, Reclaim the Streets, probably early 2000s, very early, and the Gardaí had waded in, a bit too aggressively, and had beaten up a number of people and arrested people for what was just a Reclaim the Streets party.

KAP: It takes on kind of a different meaning in that context.

FB: Yeah. So, I did it subsequently as a kind of, a reminder, and I went walking down O’Connell Street and I got to Central Bank with it. So, that was actually a very long version of it. And that got strange because at Central Bank, before Central Bank is what it is now, which is a building site, there’s a lot of teenagers who used to hang around there, so I got to there in this head guard of tubes, which I think I was still pumping up as I walked, and I got there and people were very confused, wondering, ‘What is this?’ And because there was no minder with me or anything, people wondered, ‘What is this?’ And had no way of an explanation.

And eventually, I heard a walkie-talkie near, and a Garda was saying, ‘What are you doing? Can you reveal yourself, or can you take that thing off your head?’ I can’t quite recall what he was saying, but I pulled the tubes down from around my eyes and saw this Garda, I think he was younger than me, he was very young. He was a young Garda, for sure, and he said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m doing a performance.’ And he said, ‘Well, people are getting very worried, what’s your name and address, will you stop that now?’

And I did chose to stop that now, because he’d actually... He acted as the stop, and I thought that was perfectly fine because it was getting a bit strange because, well actually, there was a huge, huge horseshoe of a crowd around looking at me, which I had no idea of. So, I could hear some rumblings in this audience of, doing something to me, sorting this fella out, whatever.

KAP: That changes the dynamic of things very quickly.

FB: People were generally freaked out by it, some people were curious, so the Garda … I thought, ‘Well, okay.’ His action has created an ending, I don’t need to persist with this. I’ve clearly got an audience, if that’s what I was looking for.

KAP: I just think too that, that work is interesting, in terms of like … this idea also of herd mentality, you know, how people act or how people are spurred on by a reaction to something that then spirals out of control. Or this macho-masculine, aggressive behaviour that people engage in sometimes to represent themselves in certain ways, in certain circumstances. …It’s kind of an interesting commentary on, maybe what it’s like to be a young man and to try and navigate your way in the world.

FB: Yeah, I think, like I did it those few times again because I think it is still relevant. I still have the thing, maybe I’ll take it out again, it still happens for sure and it doesn’t take much for that accident to happen. And people just don’t really appreciate how vulnerable the body is, and especially when they’re outside, or concrete, or falling and banging your head on concrete. It’s not the punch that does the real damage, it’s often the drop.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: You had a sound installation at Central Bank and another as part of ‘Sculpture on the Shannon’, which was in the Cratloe Woods in County Clare in 1991. What can you tell me about those works?

Fergus Kelly: That’s right. They were really simple pieces in so far as I was inserting sounds into an environment that shouldn’t exist there. By that process, I was hoping that people’s idea of what was happening would be slightly reconfigured or that their impression of the general soundscape will be slightly shifted. I think with the Central Bank, I installed speakers on ... you know the way the Central Bank building at bottom section there is an overhang? We had access through a cherry picker to those panels and I put speakers up in there. I think I had some wildlife sounds, stuff that couldn’t occur in the city … I think crickets were amongst the sounds. I think sonar might have been used in Cratloe, and again, it was just a simple exercise. It’s almost an ear cleaning sort of thing... And also the sounds occurred at an ambient level so that they blended in with the surrounding sound. They weren’t broadcast in the sense of being played loud. They were just inserted into the landscape. So, I’ve no idea how they worked or what people’s response was to them ... because there’s no way of monitoring.

Then the other thing too, I didn’t want to talk to members of the public because then it becomes a thing. I’d rather the idea that it’s something that people had the experience but they didn’t really know what they were experiencing. And certainly I didn’t want them to think of it in artistic terms. It was just something along the lines of - ‘Oh, I was in town today. And I could swear I heard crickets.’ I suppose if somebody heard it like that, and it was a mystery, it’s a success because it’s something they experience and it doesn’t have to be experienced as part of an artwork. It’s just a way of making people think about sound and about the environment. The sonic environment, not from the environmental point of view.

KAP: What about the selection of Central Bank was there any significance in that location in particular?

FK: No, I think was just one of a number of locations we were given by the SSI. So, I just thought this would be interesting. There was a lot of foot traffic of people through that.

KAP: Yes. It is quite a busy area, especially during the day.

FK: It was ideal for what I want to do.

KAP: Tell me about this other work that you did through the Sculptors’ Society of Ireland, which was part of the ‘Ireland and Europe’ (1997) exhibition, it was a sound installation in the Iveagh Gardens. As part of the exhibition also you got to select one European artist to make work?

FK: That is when I selected Max Eastley. That was great. We were paid to go over to London to meet our respective artists and then they developed a project for Dublin. Max made these beautiful Aeolian kite sculptures with this particular type of elastic that he uses. I think they were really light wood, like doweling rods in a cruciform shape and then the elastic would be around the edges of this. It made a kite shape outline. He had these coloured tassels coming off it. Visually it had this particular presence but when the wind went through them it, it had this lovely ethereal sound. It was just a ghostly sort of presence, really beautiful. And they were up high over an area of the gardens at the back.

KAP: And what was your work for this project?

FK: I set up a series of speakers throughout this wooded area that backs on to the rear of the concert hall. I developed a piece where, again, I was taking that starting point of inserting sounds in a surrealistic sort of sense that they shouldn’t exist there. I recorded them on location, then went back to the studio, processed those sounds as they existed in the gardens with the sounds of the gardens. I made a new composition with that, brought that back up to the space, played that for a number of days, recorded that, brought it back, did the same thing. So, it built up over time and became this quite rich soup of sounds recorded and layered over that period of time.

That was a nice opportunity to experiment with an environment and period of time where work could be developed and it wasn’t just a static piece. It was constantly developing. As it was more processed, it was a bit like doing a photocopy of a photocopy. It just became richer and denser. All the sounds that were happening in the gardens were layered in amongst that and it became almost a form of sonic weather or something. It was sort of like a little microclimate. It was nice to be able to create something over about two months or so. This would have been opening late August and finishing about mid-October. So you’re having a change of season as well and there’s a sense of moving through different periods of time that was more heightened. It was a large enough wooded area, I would say it would have been a good 60 to 80 metres maybe. So, again, it was a real environment. I spread the speakers throughout that space. As I say, it was really nice opportunity to develop work in a unique environment.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: I wanted to ask you then about this major collaboration that you did, ‘the Appearances Project’ with Pauline Cummins and Sandra Johnston. I want to talk a little bit about your part of the project, which was in Cork.

Frances Mezzetti: ‘Fathom’. I was doing an art therapy course in Cork in 1999, it was about six months long. While I was there, I was looking around for a place to work, and I'd just walk into places. I saw the Harbour Commissioner's office, and I walked in, and nobody stopped me. I looked around and I saw the board room. It was very ornate with beautiful ceilings, plaster work, columns, beautiful decor. There was one table on a platform, it was beautiful mahogany and a semi-circular table. Beautiful piece of carpentry. Just gorgeous. Lush carpets, tables, and chairs, and paintings around. On the board, there was the names of all the board members, but it was gilded. It's what my father did, he was a sign writer. As soon as I saw that ...

KAP: You were drawn to that?

FM: I knew that was my place for my performance. It became about my great-grandfather; the story was that he went away to sea and was lost at sea. … He disappeared when my grandfather was seven. So, my grandfather was in Artane Boys orphanage from the age of seven to twelve for stealing bread I believe. It started off with that. I wrote to the Harbour Commissioner’s Office, I have a letter here from the board saying, ‘No, we can't give you permission to work here’ on this lovely Port of Cork paper. I figured that if I kept going back and saying, ‘How are you doing?’ I would eventually get permission.

KAP: You’d get into it in a different way rather than the formal request ‘Can I work here?’ You just started making your interventions into the space anyways.

FM: Yes… As soon as I started collecting stories, I put it out in libraries, that if anyone had the story around the port of Cork or the Custom House, they could contact me. I met people in the street, went into the local bars where the dockers would be. I gathered stories that way.

KAP: It developed really organically in terms of getting these collecting stories.

FM: Yes. On the South Mall in Cork, I remember sitting on the seat, and this woman sitting there as well, and I was telling her what I was doing. We chatted, and she ended up being a participant in it.

KAP: The interest in the Port of Cork is not only based in your personal history of your great grandfather being lost at sea, but is it also an interest in these stories that construct a certain type of knowledge around people that go to sea, or even shipping practices, or commerce?

FM: Well, I was looking at stories that in this boardroom that decisions would be made that affected the workers and I was wondering how can their stories be brought into the boardroom? It was an attempt to reverse the order. That was the background. I tracked different people; I think I had twelve people. I had all these stories. There was one of these junk boats docked in the port, I asked them ‘where are you from?’ It was a husband and wife from South Africa; they built the boat themselves. She had a sewing machine on board that she used to make crafts to help them as they went around the world. She bought her fabrics in Madagascar, somewhere like that…. I collected stories from them about their ship turning over on the Coral Reef and how they prayed for a miracle and the ship righted itself. I bought a sewing machine in an antique shop to witness their story.

I was working with sails, a kind of a calico. And because I was referencing my father as a signwriter and the Mezzetti line, I used sign-writing to put their stories onto the fabric with a brush. For each one I gave them an excerpt of their story. That became part of the performance where I used them and as I moved around the room it became like a sail. We presented it to them, folded it like you do in a military fashion, and presented it to each of the story givers, or the representative of story givers.

Sandra was working on the level of balancing on the edge of the table. That bringing that sense of working on the edge of things, and that element of risk. I couldn't tell you what was in her mind, but it was balancing with the language I was using, and she also carried these sails around and presented them as well. Pauline had a water bottle where she poured out water for each person as part of the link with the water and the sea… She made beautiful movements throughout.

I was doing a kind of dance. I thought to use the room, and give the history, as much of the history. I positioned myself at the painting of the ship at sea. Then I moved towards the chairman’s table… I stood on top of the table again. It was this very precious table with someone standing on it. The performance was very light and breezy in the beginning, and then it became more sombre.

I was sewing, again, because it has a lovely sound when you're winding it and a rhythm. One of the stories was during the war, his father was trying to get back to Ireland, but they were being pursued by the Germans. The boats were lifting the engine on the floor. It was referenced in sound what was happening, it conveyed that sense of haste.

KAP: It is interesting to think about how all of these different temporalities came together within the context of the performance: the presence of you, Pauline, Sandra with these other people who were witnesses. But also how their stories were part of the performance adding to all these different layers of history that you had managed to build in.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: You were an artist in residence at Mountjoy Prison (1986, 1991) so two residencies, and you worked with women inmates? How important were these experiences in terms of expanding your practice into new directions?

Pauline Cummins: It was following the trajectory that I had set. Those residencies were organised by the Department of Justice and the Arts Council. They had a group of artists that they invited to take up residencies in Mountjoy Women’s Prison and Portlaoise Prison. I was being earmarked for the women’s prison, which I was very happy about. I noticed that there was a frisson around working with political prisoners in Portlaoise, and not so much about working with the women in Mountjoy and that annoyed me. I insisted that we all work in each prison, I felt it would only be right that each of the artists would have a residency in each of the prisons, because it would be interesting and comparative. That was just my personal take.

For me working with the women in Mountjoy ... it was very challenging, but very interesting. A few of my beliefs were that access to art was really important; that if you had the right match, people could make interesting art; that if there were the right circumstances, people could take pride in what they made, that would be really important, and influence their self-esteem. There was a woman teaching there, I spent a lot of time talking to her, asked her about how the prison worked- I knew nothing about how the prison worked. Part of my requests to the prison authorities were that people only came voluntarily, that they wouldn’t be forced to participate.

I organised a meeting and I made a collaged note, almost like a ransom note with the letters cut of out a magazine. It said ‘Women are treated like dirt in Ireland. Do you agree?’ We got a lot of people, and we got off on the right foot, as we all agreed women were treated like dirt, to varying degrees. We began work using women’s magazines that I felt were showing a false image of women’s lives, they were very readily available, and we could easily get a pile of them for our material. Women used these to make images of their own lives and what it was like to be in prison or what it was like to be away from your family or to be addicted to drugs or to feel it was a dead end. Some people were also involved with the writing program in the prison. We made a book of the collage images that were colour photocopied, which was expensive at the time, and their poems and their writings. We also made large images of their collages that they could hang in their cells. I felt it was really important that people admired what women had done, that they saw it as real.

KAP: Was there the sense that there were still opportunities for... or a sense of hope for people who may have come from marginalised backgrounds or who have experienced social inequalities, and although they may be in that setting, they could still produce something positive?

PC: Yes, the idea was to achieve something.

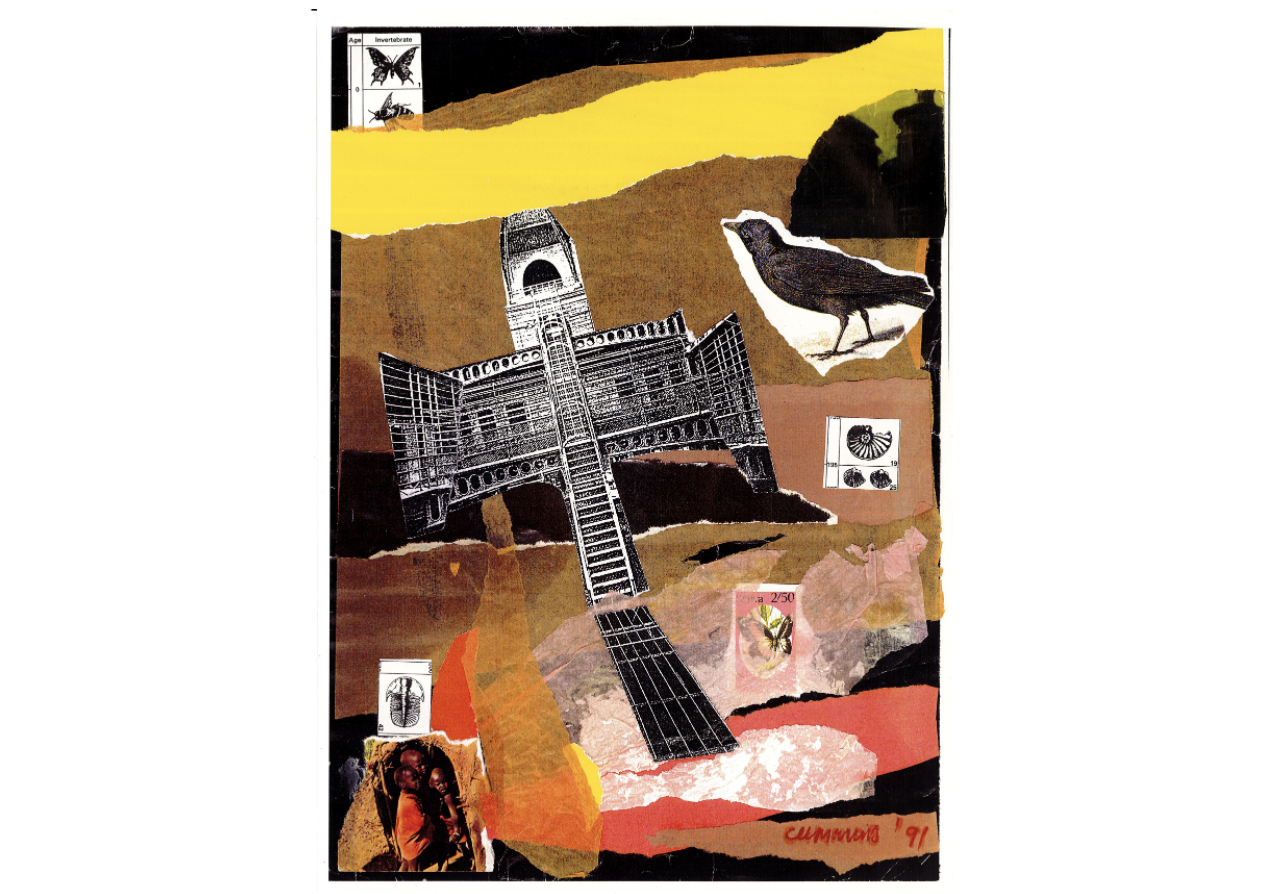

KAP: I have an image to show you, which I have sourced in the NIVAL archives, of a different collage. I’m wondering, is there any relation here? I was really excited when I came across this, because it relates to ‘Changing States’ (1991). Can you tell me a little bit about this?

PC: I was working a lot with collage and this was from 1991, it would have come from that time. It relates to what I eventually did in Kilmainham Gaol, which was using images for reflecting on the Victorians and their interests, and the amateur scientists that evolved and were very influential during the Victorian period, and the architecture and how it changed. I was amused how we could make this, as you know, this is an image of the prison, and to make it look almost like it was taking off like a bird. But really, it was just little bits of references.

I made a big piece which had an image of an Archaeopteryx on it hanging in the middle of the prison, and they’re related to crows, and then these little fossils refer to the period of Victorian study and interest. The architecture was a vast improvement on prisons, in that it was light and order, where there might have been more chaos and dungeons beforehand. It was very much of its time.

KAP: Looking through the things that you’ve done, it just struck me as two different kind of projects within prisons, both relating to women in some way. I just thought that maybe there’s a potential connection here?

PC: Really well spotted!

KAP: That brings me to ‘Changing States’(1991) and the idea of metamorphosis and the gigantic sculpture that you made in situ. What was it like to work on that in Kilmainham Gaol on site?

PC: It’s quite performative as well. It was very time consuming. The only way we could get the armature of the sculpture in was to cut it in four parts to get it through the doors into the prison. Then it was welded in place, and I painstakingly covered it with these little pieces of tissue paper, because I wanted that translucent feeling that pupa have. I had three children at the time, so I didn’t have that kind of space to work in or the time to work with them. It was good that I could get in there in the evening and work away. … But it was lovely to be in the gaol, and the sounds and the space really influenced me because I went on to do two different performances in that space. And I know that space very well. And sound, live sound, became a big part of my practice. Those kinds of spaces just cry out for live sound.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: Tell me about ‘Irish Days II’ (1994) and going over to Poland – I know this was an important turning point in your development as a performance artist.

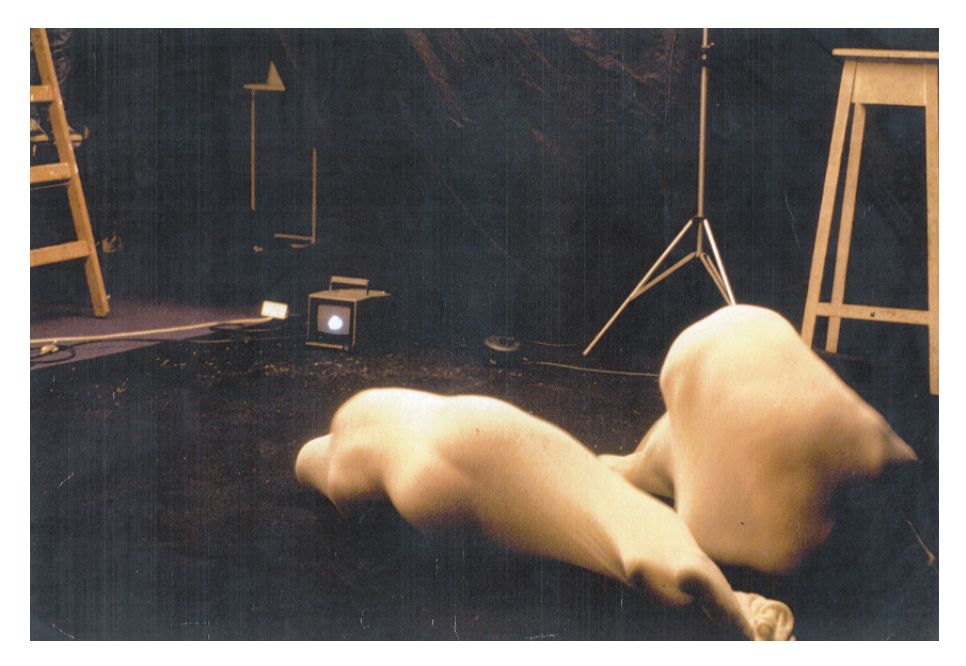

Sandra Johnston: Well, I had graduated in September 1992, and I had only been out of college for a year when I received the invitation from Brian Connolly. I had made the decision to remain living in Northern Ireland, and we were setting up Catalyst Arts at the time. My experience of performance art at that point was almost non-existent, just two experiments while I was doing the master’s course. Mostly I was working with photography, especially slide dissolve units, making synchronised projection pieces - which was already an outdated analogue technology. To backtrack for a moment, when I went to do the MA in Belfast (1991) my grandmother died in the first month when I had just started the course. I completely fell apart, was artistically paralysed and couldn't do or make anything. The staff, especially Alastair MacLennan really supported me through that terrible time when I was profoundly lost, having lost my language, any language, verbal as well as visual. At that point, painting was already starting to feel fake, like a set of tricks that I had learned and could no longer repeat, and it was in that intermediary period of crisis that I started to explore physical gestures as a different approach to retrieving memory – explicitly the gestures I connected purely with my grandmother. I didn't make any good work on my master’s course. But to give myself some credit I used that year to dismantle everything that I thought I knew about art. So, I felt like Irish Days was my second chance, and there was some sense of respect within the invitation that was crucial to starting to build self-belief.

What I made was a slide dissolve piece called, ‘To Kill an Impulse’ (1994). The work was a homage to Margaret Wright, a woman who was murdered in proximity to my home in east Belfast, and within a couple of days of having myself suffered a brutal gang attack on a sectarian interface. It's been quite a hard work to grow old with, since I made that work at the age of 24, in a psychological crisis that deteriorated rapidly into anorexia. I've always acknowledged the intricacies of it in terms of the ethics of reusing and appropriating images from the media, I was somewhat naive about the full implications of that, but equally, it’s important to remember that the news coverage at that time was completely saturated with invasive coverage of the Troubles – it was our daily normality. The actions that I filmed of myself were shot in skips of detritus, on wasteland, they were raw improvised actions – an irrational coping technique to address the inner pain. Different kinds of vulnerability emerged in the actions I shot of myself, which were about relating across to the pain concealed in the media images, where I took care to try and hide the identity of people within the shots. Both Hilary Robinson and Jill Bennett understood that it was coming essentially from a place of empathetic engagement, an impossible attempt to connect with the suffering of those other women present in the images.

KAP: How did you install this work?

SJ: That piece of work went to Berlin. It was only ever shown once, in a basement gallery, almost like a bunker. The two projectors were on shelves suspended with wires from the ceiling, with the motors running, pumping through the slides in the carousels, so the images reflected on both sides of the room were disorientating because constantly in motion. The screen was a discarded window I found under the stairs that had an old handprint on it where the grease of somebody’s hand had caught on the glass, and then over the years, dust had attached to it. The focal point of the two projections was fixed on this handprint. If you think about it in terms of the relationship to technology and media, the fact that the original images that formed the slides were shot with a 35-millimetre camera directly off a TV screen as they were being broadcast, there are aspects of liveness retained in how the images were grabbed, literally grabbed off the screen.

KAP: I think this is maybe part of the issue around documentation and liveness, but in anything I have seen around ‘To Kill an Impulse’ it does not convey that aspect of the install, the glass screen and shelves, the handprint, it doesn’t convey that. I think that is to the real loss of people trying to understand the work.

SJ: Yes, it is a loss. Both sets of images passed through each other, then ricocheted against the back walls and the whole room was visually in a kind of tremor where these images of fear and grief became both present, and yet, destabilised.

Then I made the decision going into Poland to carry nothing prepared with me, to just trust what would come. That approach was connected to the ethos and attitude conveyed by Brian Connolly. And performing ‘Scouring’ is still one of those important moments that I can't really describe. For the first time I had gone from making performance privately to camera, with the camera tied to a stick in the middle of a field, or in the backseat of a car, to having, not only an audience, but a knowledgeable audience be there with me, and actually the extraordinary intimacy and love that I felt through that contact. The building was important, because it was a witch's tower, where women since the 13th century had been incarcerated and then drowned in the river outside. The saliva which was central to the action was about the river, and again, it was about fear.

KAP: So, you had a thread held in your mouth which ran over the four floors?

SJ: Yes, it ran through holes in the floorboards, when I first looked at this building as a site, I noticed a small hole in the floor and the concept came to pass a thread through the building and to attach it to my tongue, with the saliva running down it becoming a substitute for speech. However, since it was my first live performance, I hadn’t understood the impact of just how nervous I would feel having an audience watching me. I didn’t know that when you are afraid you physically cannot make saliva – the shutdown is a survival mechanism. So, when it came to performing it live the intense effort to salivate meant that my teeth cut the inside of my mouth, and it was a mixture of saliva and mostly blood that was running down the thread towards a bowl of black engine oil – a dead inert material placed in the bowl on the bottom floor.

I had picked up burnt wood from the beach and brought a stack of it to the tower. I was starting to install it, but was being too precious, unsure about the limits of what I could do in a historical building. Anne Tallentire looked in at what I was doing, and she said, ‘you just need to be bolder’, and she was right. After she left, I set to work developing a more sculptural handling of the space, I smashed large pieces of burnt wood onto the floor so that they shattered leaving a series of trace drawings and then spaced in-between were metal bowls from a Russian army camp. There was a precision about how people entered the space and encountered the different layers that were in motion, so my body became just one of a number of elements, and I think that gave me confidence to understand that the entirety of the situation was the artwork not just my physical presence.

Kate Antosik-Parsons: I want to ask you about your participation in the ‘Ireland and Europe’ (1997) event.

Seán Taylor: Oh yes, ‘Insult the State?’ (1997).

KAP: Can you give me some background information on this work and its concerns?

ST: As I mentioned previously, in Glasgow I was doing a lot of work around racism, because of my involvement as a community artist. There was an organisation called the Scottish Asian Action Committee that I used to work for because I had a camera. I used to go on marches and document members of the British National Party and other far right organisations that would try and attack marches. I finally gave up after giving the shit kicked out of me at a march in Edinburgh, it was just one beating too much and they were beginning to target me as well. And so that interest in racism came through in a lot of my own work. I did a lot of multimedia work around the subject of the European Union's attitude towards racism and this beginning of what I saw as ‘Fortress Europe’, which has now come to pass.

KAP: There is a symmetry with what's going on now.

ST: I always seem to be ahead of curves. I was reading a story in the newspaper about in Germany, that you could be prosecuted for insulting the State. And then, a number of months later, the European Union passed a very similar piece of legislation and the Irish government was also talking about enacting that piece of legislation that you will be prosecuted for insulting the State, under certain circumstances, for example, like burning the Irish flag. In Germany it was more to do with the rise of the right and this burgeoning love affair with Nationalist Socialism that was coming up, which hasn't seemed to stop them at all.

I thought this would be interesting because it was a European Union sponsored exhibition, the Department of Foreign Affairs were involved and because also the Minister for Foreign Affairs at the time was Ray Burke, who was facing allegations of corruption, and the rumors about him were just starting to circulate. I thought that this would be a good opportunity to fly an airplane past the Department of Foreign Affairs, on the day when this meeting is taking place for all the European ministers to address this notion of insulting the state and what are the implications for that? But the Sculptors’ Society of Ireland strangely enough had serious issues with the banner. Aisling Prior was involved, we laugh about it now, but back then, Aisling was like, ‘No way, we like the idea, but no way can we leave the banner like that’. Actually, I had an exclamation mark on the banner.

KAP: So it wasn’t posed as a question ‘Insult the State?’ but it was more of a statement?

ST: Aisling’s compromise was to pose it as a question. Which I didn't want to do, but I thought I am never going to get this done if I don’t.

KAP: Amazing, though, a dispute over punctuation.

ST: Yes. I meet Aisling all the time and we still talk about it, but it was quite heated at the time. I was adamant that my exclamation mark was staying, and Aisling was adamant about the question mark. In the end I gave in, I thought, it was more important to get the thing up in the air and fly it around that day.

KAP: My understanding was that it was also flown over Croke Park as well. That has really interesting implications in terms of the history of Croke Park in relation to the history of the Irish State.

ST: Absolutely. We had to get special permission from air traffic control, we have to we have to give them the route. It went up on two days, the opening of the exhibition and the All-Ireland Hurling final day. The whole idea was that there would be no publicity, it would just turn up and people would question what is that all about. Then it might trigger the question and they could go to the website to find out. Croke Park was amazing, because I was watching on television and the camera went up and there was the banner flying across the sky. I though that’s fantastic.

KAP: Live broadcast! You do have an interest in critiquing nationalism. I’m thinking about some of the other works you did for Infusion: the National Review of Live Art ‘Dancing for Spiritual Freedom’ (1999). The description of which reads ‘moving statues meets River Dance, embracing 80s, disco kitsch, icon worshipping snot green nationalism’.

ST: Yes, I basically went around the country photographing as many monuments as possible. And what struck me about the poses of the monuments is that they were very similar to a lot of moves people did on the dance floor. Frozen moments. I thought, well, what if you could string all the images together into a particular dance. I choreographed a dance, and then projected the images behind me. I got Richard Creasey to do the music, because I wanted that 80s dance floor feel, not the rave-y dance floor feel. I obviously dressed as kitschy as possible, and just went for it.

It was interesting, that then RTÉ phoned me up out of the blue one day, somebody from RTÉ had been in the audience and had seen it, and they wanted to commission it. RTÉ had a series called ‘Dance on the Box’, they commissioned artists, dancers and choreographers to do a one- or two-minute dance piece and they would film and show it. I submitted this, I went to Dublin, and we met the producers, and they loved the idea. I’d asked for a whole bunch of dancers to come with me as well, they were to be all dressed in leotards and we would shoot part of it, a move onsite, and then the rest of it in the studio. It got the green light, and about two weeks before we were about to start shooting… RTÉ got cold feet, they pulled the plug on it. They thought the subject matter was just a little bit too risqué.

KAP: Really?

ST: Yeah. But when you look at when you look at the ‘Dance on the Box’ series of commissions, there's not a lot there that critiques anything. It’s very much a celebration of Irishness and this was definitely…

KAP: This was posing a different form of question about ‘Insult the State’.

ST: You can't take the mickey out of Daniel O’Connell and people like that.

KAP: No. I mean, I think it's interesting to consider this work in light of commemoration and this ‘Decade of Centenaries’ that we are currently in, and how that connects with the past. Now that we have this distance, it's okay to critique, but even in 1998 or 1999, when you're doing these works, it was a bit of a different story then…

ST: I agree with you. It would have been great to have a piece done. But it lives on, and maybe it's better that it lives on in memory.